Introduction

Most people have debt. And if they don’t, they should consider having debt.

That might sound like a reckless statement, but as you will see in this ebook, used well debt is an extremely useful tool.

Of course, used badly, debt can be dangerous. So you have to get it right. The old saying is true: all things in moderation. Especially with debt.

This ebook is all about using debt well. It is an important book, because the way in which people manage their debt performs a vital role in the success or otherwise of their financial management.

For example, think about the simple home loan mortgage that virtually every person takes out to buy their own home. According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, 28.2% of Australian households hold some form of home loan (as of September 2021). Households led by people aged between 35 and 44 (51.3%) and 45 and 54 (45.2%) are the households most likely to have home loan debt. The median value of these home loans was $586,366 in Feb 2023. At the same time, the average interest rate for owner-occupied home loans was 5.1%, suggesting a median interest payment of at least $29,905 per year.

At the same time, average disposable (i.e. after tax) household income in Australia was around $80,000 a year in 2021. Putting these two figures together suggests that interest payments on home loans accounts for (on average) something more than 37% of a household’s disposable income.

You can see, then, that managing this interest expense as well as possible opens the door for increased wealth and financial security.

And that is just for home loans, which are usually filed in the ‘good debt’ file. What about debt that we usually describe as ‘bad?’ According to ASIC, the average level of credit card debt per credit card holder is $3,045. The presence of credit card debt is reasonably consistent for all ages and income types, with a dip in the incidence of credit card debt for unemployed people.

As of April 2023, the indicative interest rate for credit cards was 19.94% (Source: RBA). This suggest an average interest bill for card holders up around $600 per year.

You can see why we normally refer to credit card debt as “bad.”

Now, what about investment debt, which, history suggests, is likely to make the borrower better off? This means it is usually ‘good debt.’ Well, according again to the ATO, 20% of households have any form of investment property debt. 80% of households don’t. Interestingly, the rate for University graduates is 16%, while the rate for early school leavers is 5%. A university graduate is three times more likely to borrow to invest than someone who left school early. The median amount of investment property loans is $410,000 as of January 2022, which is a little more than the average home loan, and the indicative interest rate for investment property debt is 5.90%. This suggests an annual interest bill of around $24,190. That bill, however, needs to be offset against any extra income being generated by holding the asset (think rent for property investments and dividends for share investments).

Finally, what about personal loans, which might be good or might be bad, depending on how the money is used? For example, borrowing $10,000 for a life-saving medical procedure is good debt. Borrowing the same amount of money for an upgraded home entertainment suite isn’t. Well, according to the Reserve Bank of Australia, 37% of households have some form of debt other than home loan, credit card, HECS or investment property debt. The RBA reports a median value of $11,000 for such debt, with an indicative interest rate of 14.10% for such debts. This suggests around $1,500 of interest on personal loans each year. As we say, this interest bill might be money well-spent: it all depends on how the loan is used.

So, you can see that debt is pervasive. Read on to find out how best to manage this common element of your financial planning.

Types of debt: the good, the bad and the downright ugly

Debt is a fact of life for most people. It may come from starting a business, buying into a business, buying a home or acquiring investments. It requires careful management and control so it does not cause financial loss and pain, which is the very opposite of wealth creation.

Unless you are born wealthy, there is normally no choice but to borrow to acquire assets of any significant value. It is hard to save up $600,000 or so to buy a home. By the time you do, you will probably be looking for a retirement home.

A controlled amount of debt, used intelligently, can have a wonderful, positive influence on the quality of your life and on your net wealth position. It allows you to acquire assets otherwise outside of your reach and to benefit as the value of the assets rises and as the debt is gradually repaid.

Chapter 1: Home loan debt and how to manage it

Home loan debt is debt incurred on buying, maintaining or improving a home. Home loan debt is usually not that expensive, since the loan will be secured by mortgage over the home, and this means there is relatively little risk for the lender. Rates are currently about 5%.

Home loan debt is easily the most common form of personal debt in Australia. It accounts for more than two-thirds of total personal borrowing. The interest rate on home loans is usually lower than the borrower could achieve for other types of debt because the lender typically takes a mortgage on the home. A mortgage is a form of security arrangement that gives the mortgage holder (the lender) the right to order that the asset be sold in the event that the terms of the loan agreement are not met. Because of this right, the risk to the lender is less than it would be in other cases. Consequently, the lender is happy to accept a lower rate of return from the borrower.

Please have a look at this simple but useful video from the folks at Investopedia, which gives a good general description of a mortgage:

Sometimes, people assist other people to undertake a home loan. For example, parents may allow their children to use the parental home as security for a home loan. This is known as guaranteeing the loan. This type of borrowing is included within the range of owner-occupied borrowing.

Home loan debt is not tax deductible: it is not incurred for the purpose of producing assessable income and it is inherently private and domestic in nature. This means you have to earn more than $1 for every $1 of home loan interest that you have to pay. If your marginal tax rate is 30%, for example, then you have to earn $1.42 in order to pay $1 of interest to the lender (after you pay $0.42 in tax). Thus, a 5% home loan rate becomes the equivalent of 7.14% pre-tax for someone in the 30% tax bracket. The pre-tax rate is higher if you are in a higher tax bracket. That’s expensive money.

This is why everyone should aim to pay off their home loans as quickly as possible. Making repayments on a 5% home loan is the same as earning up to 7.14% capital guaranteed, adjusted for tax. For the level of risk (nil), that’s easily the best investment you will ever make.

The following sections discuss various strategies for best managing home loans. We recommend that you speak to us before you implement any of them, as they often require you to do some other things correctly as well. But the main objective is the same throughout: minimise non-deductible interest on your non-deductible home loan.

Ways to manage home loans

Interest offset accounts

Interest offset accounts (IOAs) are a particularly useful type of savings account. They are a standard savings account, but they are linked to a home loan. The balance of the home loan on which interest is charged is reduced by the amount within the IOA.

For example, if you owe $150,000 on your home loan, but have $50,000 in an IOA, then you will only pay interest on $100,000. Effectively, then, the rate of interest paid on the $50,000 is the same interest rate as you are paying on your home loan. This will be higher than the interest you would receive for any comparable type of investment.

This short video made by the Yorkshire Building Society explains how they work (just remember to convert from pounds to dollars!):

Interest offset accounts should be considered (and probably used) by virtually everybody with a home loan – at least, everyone who is ahead on their loan repayments. This is because when you put money in an IOA it is as if the amount in the IOA has actually been paid off the home loan. But it actually hasn’t. The money in the IOA can be accessed the same way that your normal savings can. This is usually much easier than redrawing on a home loan.

Parents, for example, who might be thinking of sending their kids to a fee-paying private high school might choose to save into an IOA rather than make extra repayments onto their home loan. This makes things as easy as possible when it comes time to pay the fees: the parents simply use their savings. The alternative, in which parents make extra repayments into their home loan, would require the parents to redraw money from the loan each time they needed to pay a school fee. At the very least, this is a hassle. It can also involve fees and charges, and a lender might even refuse to allow the redraw if the parent’s situation has changed (if one loses a job, for example).

IOAs are often used by families to help out younger members who are buying a first home. In a simple example, mum and dad (in their fifties or sixties) agree to let their kids use their own savings money to offset their son or daughter’s loan account. Mum and dad might be giving up a small interest benefit for themselves, but their son or daughter get a much larger one.

For example, the ANZ currently pays 0.5% interest on its premium cash management account, for amounts up to $100,000. So, if mum and dad have $50,000 sitting in a savings account, they will be earning just $250 a year in interest. (That interest is also taxable if mum and dad are taxpayers). If their adult son or daughter has a standard ANZ home loan, the interest rate is around 5.2%. So, if the $50,000 is used to offset the kids’ home loan, the kids save $2,600 in interest each year. And, of course, if the kids pay tax at 30%, then they need to earn more than $3,700 in order to pay $2,600 in interest.

Putting the $50,000 into an offset account earns an effective pre-tax amount of $3,700. This is easily the best return available for that $50,000. The son or daughter could even pay the parent $250 (or something more) to reimburse them for their lost income – and still be more than $2,300 better off.

There does need to be some caution: the savings account will need to be in the daughter’s name, and so it would make sense for there to be a loan agreement in place between the daughter and her parents. But this is quite easily managed and it is easy to give mum and dad plastic cards that allow them to access the money without needing to involve their daughter.

So, if you or someone you love has a loan, you should consider an interest offset account.

Superannuation and home loans

Ultimately, private housing must be bought using after-tax dollars. The deposit used to purchase a private residence, for example, must be saved after tax is paid on the purchaser’s income. The principal and interest payments on the loan must also be paid out of after-tax income. Ultimately, the whole property is paid for after-tax.

Because of this, people who face lower tax rates require less pre-tax income to buy the same amount of house. The following table shows how much pre-tax income is required to buy a $500,000 property, when various marginal tax rates apply.

| Tax Rate | Pre-tax Amount Required | Tax Paid | Amount Remaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | $500,000 | 0 | $500,000 |

| 15% | $588,235 | $88,235 | $500,000 |

| 19% | $617,284 | $117,284 | $500,000 |

| 32.5% | $740,741 | $240,741 | $500,000 |

| 37% | $793,651 | $293,651 | $500,000 |

| 45% | $909,091 | $409,091 | $500,000 |

What this table shows is that the same property does not cost the same amount for people with different marginal tax rates. A person paying no tax only has to receive $500,000 to buy a $500,000 property. A person paying tax at a marginal rate of 45% has to earn more than $900,000 to buy the same property.

Have a particular look at the second row. This is the 15% tax rate this is payable on deductible super contributions into a super fund. The point of the table is this: if families make deductible super contributions into someone’s super fund, and then withdraw these contributions tax-free when the relevant person reaches the age of 60 and use it to pay for repay the home loan, the family only need to earn $588,000 pre-tax to buy the $500,000 property.

So, in many cases, and especially if you are approaching the age of 60, it makes sense to increase super contributions rather than repaying your home loan. In that case, you would make paying off the home loan a retirement goal.

Prioritise repayment of the expensive home loan

As we saw above, for taxpaying borrowers, home loans are actually more expensive than the interest rate suggests. This is because the home loan is used for a private purpose, and it is therefore not tax deductible. This means you have to pay tax before you pay interest. For someone in the 30% marginal tax bracket and paying 5% interest on their home loan, the effective pre-tax interest rate becomes more than 7%.

In contrast, if a loan is used for a deductible purpose, such as buying an investment property, then the interest is deductible. The interest rate paid to the lender is the same as the effective after-tax rate. The effective after-tax rate is therefore often cheaper on the investment loan.

So, a home loan is generally more expensive than an investment loan. This means that you should prioritise repaying the home loan wherever possible. A simple way to do this is to make sure you use your deductible debt facility to pay any expense that that facility is appropriate for. For example, council rates for an investment property can and should be paid using the deductible debt facility.

Using debt to pay as many of these expenses as you can will free up as much of your cash flow as possible. This freed up cash flow should be used to retire your non-deductible debt.

In this way, every extra dollar that you draw on your deductible debt will be offset by the repayment of an extra dollar of your non-deductible debt. You borrow a dollar on one loan and repay a dollar on the other loan. The total debt will not be increased, but the mix of debts will have changed. The less expensive debt will be larger than it would have been otherwise; the more expensive debt will be lower. This means that your total debt has become cheaper.

Remember: the deductible debt can only be used to pay expenses that are appropriate to be paid using that debt facility – basically, debt used to acquire or manage income-generating investments. It cannot be used for private purposes.

AMP refer to this as ‘debt recycling’ and you can read their thoughts on it here. As it happens, ‘debt recycling’ is a misnomer. The debt is not recycled. One debt is removed and another is created. They are two different debts. The second debt is entirely new. But let’s not quibble – the AMP is better at developing strategies than it is at naming them.

Just leave it

This might sound like a radical, reckless idea, but one strategy is to simply leave your home loan un-repaid. It is not the best strategy, especially as you continue to have to pay non-deductible interest. But it can make good sense in some cases.

This strategy requires you to use an interest only account. We describe these more fully below in the section on investment debt, because these loans are most often used to service deductible debt. But interest only loans can also be used to finance personal debt such as a home loan as well. You just need the lender to agree to make the loan interest only.

The idea here is usually that the value of the home will rise over time. As long as the debt does not rise, the home-owner becomes more wealthy. Consider the following example: in 1999 a couple borrowed $168,000 to pay for 80% of their new home, then valued at $210,000. Their equity in the home was therefore worth 20%. By 2023, the home had increased in market value to $800,000. If the couple had simply met the interest expense on the loan, then they would still owe $168,000. But their equity has risen to now be worth 79% of the value of the home. They could sell the home, pay out the debt and buy a cheaper one outright for $632,000. Or, they could continue to service the loan and remain in this house, perhaps forever. It would then be left to their estate to pay out the loan after they die.

By 2016, if interest rates were 5%, then the interest on the loan was $8,400. This was just 1.2% of the $800,000 that the new home was now worth. So, if the home continued to increase in value by at least 1.2%, then this couple would continue to become more wealthy even without paying out the debt.

Consider another elderly gentleman who owned a home worth $300,000 in 2014. He was eighty years old, and the home needed some modifications to enable him to keep living in it. The family sought government funding but he did not qualify because he owned his own home. Happily, the family saw a financial adviser who recommended that they borrow the $20,000 needed to modify the home (the elderly gentleman did not have any spare cash). Interest rates were a bit higher back then and the debt cost around $1,400 a year to service. This equates to a bit less than $28 a week, or $4 a day.

The modifications were made and the man continued to live in the home for another nine years before he passed away. By then, the home had increased in value to $750,000. The estate sold the home and paid out the debt. Over nine years, the property increased in value by $450,000. This equates to approximately $136 per day – much more than the extra $4 that the man had to pay to service the debt.

Many people choose to discontinue repaying principal during the peak cost years of their life – typically when they have teenage children. The idea is to take some of the financial pressure off by extending the period of time it takes to repay the home loan. This strategy often sits more comfortably with families that have reduced their initial loan and/or experienced some capital growth, such that they have created equity in their home.

Of course, leaving debt unrepaid does involve risk: property prices can fall, especially for high-supply properties such as apartments, or new homes which can fall in value as the home stops being new. The strategy only really works if the property always rises in value. Relying on capital growth to repay your debt is not for everyone. But in certain circumstances, it is worth considering.

Chapter 2: Other personal debt and how to manage it

As we saw in the previous chapter, home loans are the largest single type of personal debt. But there are other types. We discuss the two main types here: personal loans and student loans.

Personal loans

One type of personal debt is a simple personal loan. These are typically loans for smaller amounts and are typically used for private purposes like buying a car or taking a holiday. (That said, they can be used to finance business or investment activities. But we will assume in this chapter that the personal loan has been used for non-income producing purposes).

The loans are typically unsecured and attract interest rates that are much higher than you would pay on a secured loan such as a home loan.

In many ways, personal loans should be managed as if they were home loans. They should be repaid as a priority if you also have cheaper debt such as a home loan, and you could think about using the super system to repay personal loans if you are approaching or have reached preservation age.

If you have any spare cash, this should usually be used to repay a personal loan. Similarly, if you have the capacity to draw further on a home loan, then you should do this to pay out the personal loan. This is replacing one type of private debt with another, but because the home loan has a lower rate of interest you will be better off.

The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) have substantial information on their website about personal loans. You can read the material here. They even have a personal loan calculator that you can use to calculate your borrowing capacity and your repayment capacity. You can use the calculator by clicking this link.

Student loans

Student loans are loan monies extended to tertiary students to help pay the costs of their degree or diploma. In Australia there are two main forms of student loans. These are HECS-HELP, which are typically available to students studying at undergraduate level, and FEE-HELP, which are available to people studying in a fee-paying course.

HECS-HELP

HECS-HELP loans are available to eligible students who hold a ‘Commonwealth Supported Place’ in a higher education facility such as a University. Australian citizens and holders of particular visas (such as permanent humanitarian visas) are eligible for HECS-HELP assistance.

The HECS-HELP system is a generous one and most University students make use of it. This is the case even for those students who could afford to pay their tuition fees ‘upfront.’ Accordingly, most graduates graduate with at least some level of HECS-HELP debt.

HECS-HELP debt is quite simple to manage. Repayments are made via the taxation system, with the ATO demanding repayments when your income rises above the compulsory repayment threshold. This threshold is currently just over $54,000 a year. No repayments are calculated on the first $54,000 that a person earns. Amounts above this threshold are taxed at an additional 4%, with the tax rate increasing by 0.5% for every $6,000 or so of increased income. A person earning taxable income of $70,000, for example, will be paying 5.5% additional tax on the last dollar earned.

You have no choice about repaying this debt. If your income exceeds the threshold, the ATO demand a suitable amount be repaid.

Strategies for managing HECS-HELP debt

While HECS-HELP is a debt, the typical ‘strategy’ is that people should not pay it off any sooner than they have to. Historically, people have received a bonus for amounts repaid voluntarily. The bonus is currently 5% on amounts of $500 or more. So, if a person repays $1,000 voluntarily, their account is reduced by $1,050. However, the capacity to do this ended at the end of 2016, after which there is now no incentive for early repayment.

Even with the incentive, it was rarely in your best interests to repay HECS-HELP debt any faster than the ATO request. This is because the debt is effectively interest-free, with only the inflation rate being applied to outstanding amounts. This means there will almost always be a better ‘return on investment’ to be had elsewhere. For example, if you have any form of interest-bearing debt, such as a credit card or home loan, you will achieve greater savings in future interest by retiring these debts first.

If you do not have any other forms of debt you would still be better off directing money towards the accumulation of assets, through such avenues as superannuation.

What’s more, unlike virtually all other forms of debt, if you die with a HECS-HELP debt your estate is only liable to make the repayment that would have been payable in the year of death. All other HECS-HELP debt is cancelled. Dying with a HECS-HELP debt is the same as dying with no debt. (From time to time there is talk of changing this, but as yet the situation remains that HECS-HELP debts are cancelled upon death).

So, it makes sense to wait until you have to repay this debt, and to not repay it any sooner than that.

FEE-HELP

FEE-HELP loans are those made to Australian citizens and some other Australian residents who are completing an eligible course of study. The difference between FEE-HELP and HECS-HELP is largely to do with whether the University place occupied by the student is a fee-paying one. If so, FEE-HELP is likely to apply.

The FEE-HELP facility is generous, but not as generous as HECS-HELP. Unlike HECS-HELP, which is uncapped, FEE-HELP is capped at just under $100,000 (it is about 25% higher for medicine, dentistry and veterinary science studies).

FEE-HELP debt is repaid at the same rate and by the same method as HECS-HELP: the ATO levies a repayment amount on all income above the compulsory repfiayment threshold of just over $54,000.

FEE-HELP and HECS-HELP do have one difference: where FEE-HELP is being levied on a student in an undergraduate course, other than one being provided through Open Universities Australia, there is an additional fee to the value of 25% payable by that student if they use FEE-HELP. Accordingly, these students are generally better off paying their fees upfront if possible.

The loan fee is applied ‘as you go.’ That is, the loan fee is applied at the same time as the FEE-HELP debt is created. From that point on the loan fee is added to the overall debt and repaid in the same way. The loan fee is not, however, included in the cap of just under $100,000.

Strategies for managing FEE-HELP debt

The strategies for repaying a FEE-HELP debt are the same as for HECS-HELP: basically, don’t repay the debt until the taxation office makes you do so. The reasoning is also the same: no interest is charged on the debt (it is simply indexed to inflation) and so there is almost always a better use of money that would be used to accelerate repayments.

Chapter 3: Consumer debt and how to manage it

Consumer debt is debt taken out to buy consumer products and services. Consumer debt is usually very expensive – some credit card debts charge up to 20% per annum – and is not tax deductible because it does not relate to assessable income. Again, if you pay tax at 30%, the effective pre-tax rate on a 20% credit card becomes almost 29%. Looked at another way, if you pay interest on a credit card then you effectively increase the price of everything you buy by 30%. Something you buy for $1,000 actually costs you $1,300.

And if you do not pay the card off quickly, the price actually doubles every 2 and a bit years.

What’s worse, credit cards are typically used to buy consumable goods and services, which fall in value over time – and especially as soon as you buy them. This means that if you pay interest on credit cards, you have increased the price of something that immediately falls in value. We call this a ‘double-whammy.’

Some consumable goods and services are unavoidable. Food, shelter, clothing, and health are all things people need. They are often referred to as non-discretionary consumable items, as the buyer does not really have the discretion to decide whether to buy them. But other consumable items are what is known as ‘discretionary.’ If you do not buy them, you will still be OK. Using a credit card to buy discretionary items is a really bad idea.

Not all credit card purchases attract interest. Most cards allow an interest-free period. If the user of the card pays the credit card bill in full before interest charges are applied, then they do not pay interest. However, only 30% of credit cards are repaid within the interest-free periods, meaning 70% of credit card users pay interest.

The following sections discuss various strategies for best managing credit card debt. We recommend that you speak to us before you implement any of them, as they often require you to do some other things correctly as well.

Using credit cards well – transactors and revolvers

People who never pay interest on their credit card use the card merely for convenience. Credit cards allow payment to be made in various settings, including over the phone and online. Essentially, the credit card provider works as an intermediary, removing the need for the purchaser and the seller to have a direct credit contract between them. Instead, the purchaser and the seller each have a contract with the credit card company. It makes life much easier.

People who use credit cards for convenience are often referred to as ‘transactors.’ Investopedia defines a transactor as:

A consumer who pays his or her credit card balance in full and on time every month. Transactors do not carry a balance from month to month; they always pay their credit card bills in full by the due date. Transactors do not pay interest or late fees.

There is no problem in being a transactor. You are not really borrowing money for these purchases, because you never pay interest. You are using the card merely to make life easier – which often improves our financial bottom line, as well. You might pay a relatively small annual fee for the convenience of the card, but this fee can often be offset by the rewards program that the credit card provider make available.

Most transactors arrange for the balance of their credit card to be automatically repaid using direct debit each month. This means that they never incur interest on the card.

Consumers who do not pay the balance of their credit card off each month, and who thereby incur interest on their card, are sometimes referred to as revolvers. This word is used because these people just go around and around in debt. Their credit card debt is real debt, and needs to be paid off.

What to do if you are a revolver

So, be honest: are you a transactor or a revolver? If you are a revolver, then you really should do something about your credit card debt. Remember, we saw above that the effective pre-tax rate of interest on credit cards can be as high as 29% (and this is for people in the 30% tax bracket. The effective rate is higher if you are in a higher tax bracket). But there is some good news: if you can pay off some or all of your interest-bearing credit card debt, you earn a guaranteed 29% pre-tax return per year. This is simply the best investment return you can get, especially seeing that there is no risk involved in paying off debt.

So, what can you do to reduce or eliminate credit card debt? Well, firstly, if you have the cash, use it to pay off the debt. But, given you have the debt, we assume you do not have the cash. In that case, the best way to reduce credit card debt is usually some form of consolidation. Consolidation means combining one or more high interest loans into a loan with lower interest. Consolidation strategies can include:

- Consolidating credit card debts by redrawing on a home loan;

- Consolidating credit card debts by establishing a personal loan to pay out the credit card/s; or

- Consolidating credit card debts into a new credit card facility offering interest free periods on credit card transfers – and then working feverishly to eliminate the debt during the interest-free period (after which the credit card issuer starts to charge an even higher interest rate).

Regarding number 3, we cannot stress enough that it is a temporary measure only. Don’t consolidate the debt and then leave it unattended. You should only use this strategy if you are able to repay the entire debt during the new card’s interest-free period.

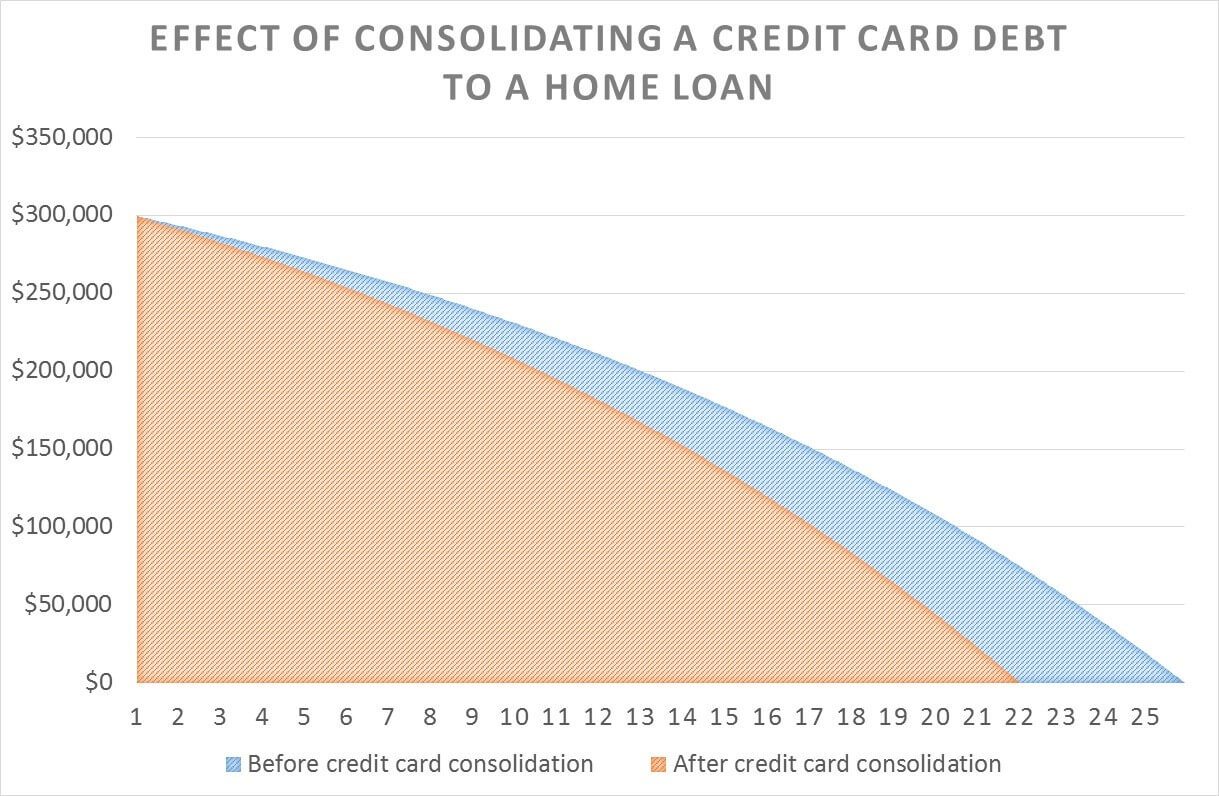

Have a look at this graph, which shows the effect of consolidating a credit card onto a home loan. The graph assumes that, having used the home loan to pay out the credit card, you then use the money that you would have had to repay on the credit card to repay the home loan. Because you are no longer spending money paying interest on the credit card, you actually reduce the length of the home loan by more than 15%.

What the graph shows is the expensive credit card debt restricts your ability to repay your home loan as well. Sometimes, consolidation cannot occur. But there are still some things that you can do. Consider the following:

- Where there is more than one credit card: target the card with the highest interest rate applicable to be repaid first;

- Where there is more than one credit card: target the card with the lowest balance first. This might not be as good as the option above, but a lot of people find that they are encouraged by the ability to completely repay one balance and this is the best way to get started;

- Negotiate with the credit card provider; or

- Sell something and using the proceeds to pay down debt.

This last step might seem drastic, but if you sell something for $1,000 and then use it to pay off debt, you not only have less debt: you save yourself an extra $300 or more in pre-tax interest. This means that selling things increases the value of them. Selling something for $1,000 makes you $1,300 better off – and this is just in year one.

Credit cards and small businesses

For transactors, credit cards provide a simple way for a small business to manage its record-keeping. Consider a psychologist operating her own small business. She will probably have a private credit card which she uses for personal expenditures such as groceries or petrol. If she uses the same credit card to pay her business expenses, then at the end of each month she needs to manually review her credit card statement to identify those expenditures which can be treated as deductions when calculating her business profits.

A better way is to acquire a second credit card and to use that credit card exclusively for the bills which apply to the business. By doing so, the monthly credit card statement becomes the record of the various expenses it was used to facilitate. These days, the statement is usually digital, and the information can be provided directly to her financial adviser or her financial management software.

If the business has a loan facility such as an overdraft, she can even organise for that facility to be used to pay the credit card balance by direct debit at the end of each month. Direct debit should always be used, to ensure that interest is not incurred on the credit card. It also means you will never forget to pay the balance. This ensures you will be a transactor. Provided that the expenditures were for legitimate business expenses, this will not compromise the deductibility of the interest on the overdraft.

Many people who use credit cards in this way make the ‘work’ credit card a completely different colour. Something as simple as ‘blue card for me, yellow card for the business’ often works well.

Chapter 4: Investment debt and how to manage it

So far, we have looked at private debts such as home loans, personal loans and credit cards. Now, let’s take a look at investment debt.

Investment debt is debt taken out to buy investment assets. These are things like investment properties and/or shares. Borrowing to buy investment assets is known as gearing. Investments purchased using borrowed money, at least in part, are sometimes referred to as ‘geared assets.’

The key difference between investment debt and personal debt is the tax treatment of the interest. For personal debt, interest is not deductible. For investment debt, it usually is. This means that a person need only earn a lower amount of pre-tax income in order to pay interest on an investment debt.

We need to make an important distinction here. When you have an investment debt, you have to pay two amounts to the lender. One payment is to return the amount they lent you. This is known as the principal, and repaying this amount is called a principal-repayment. The other payment is the interest on the amount that you have borrowed.

When we talk about deductibility, we are only referring to interest payments. Principal repayments are never deductible.

So, the interest on investment debt is typically deductible. For this reason, the basic concept regarding investment debt is this: you should only repay investment debt if there is nothing better to do with your money.

Think about this for a minute. To better understand what we are saying, remember that whenever you have debt, you have effectively borrowed money whenever you use money to do something other than repay that debt. This is because you could have used the money to pay off debt. To use a simple example:

Suppose I owe $1,000 on a personal loan. I then receive $1,000 as a gift. I have two choices. I can spend the money on the latest flatscreen TV, or I can pay off the debt. If I pay off the debt, I will not have any debt left. If I buy the TV, I will still owe $1,000. So, if I buy the TV I owe $1,000 more than I would have otherwise. I have effectively borrowed $1,000 to buy the TV.

Now extend this out to your investment debt. The interest on this debt is deductible. If I have some money, I can either repay this debt or I can use it to buy something else. If I use it to buy something else, then I have effectively borrowed to buy that item. In this case, though, I have effectively made a tax-deductible borrowing to buy that other item. This is the case even if the item is a private one, such as a TV.

This works because the original debt was used for an investment purpose. The interest on it remains deductible, regardless of whether I could have repaid it if I had wanted to.

For that reason, it would not make any sense to repay investment debt and then use borrowed money to purchase private assets.

So, what are some of the better things to do with your money?

So, you should only repay investment debt if there is nothing better to do with your money. Usually, there are such things, so let’s look at a few of them.

1. Any private thing that you would have to borrow money to afford

There is no point in repaying deductible debt if you then have to borrow money to buy something that is not deductible. For example, let’s say you have $30,000 and you need a new car. The car is for private purposes and so debt taken out to buy it would not create deductible interest. It makes no sense to use your $30,000 cash to repay deductible debt and then borrow to buy the car. You have effectively swapped cheap debt for expensive debt.

The same goes for things like improvements to your home – or even an upgrade of your home. These are private expenses, so pay them before you repay deductible debt.

The private ‘thing’ might also be to help someone else, such as an adult child. Instead of paying down your deductible debt, you might create a savings account which is offset against your adult son or daughter’s private home loan. The family is much better off to avoid non-deductible interest in the kid’s hands rather than avoid deductible debt in mum or dad’s hands.

2. Superannuation contributions

Most people cannot borrow to pay deductible super contributions. However, as we have seen, if I choose to make extra super contributions instead of repaying debt then I have effectively borrowed to make the contributions. And if the debt that I have not repaid is deductible, then I have made a deductible borrowing to pay for the super contributions.

Think about an example. You are fifty years old and you have just made the final repayment on your home loan. You also have an investment property loan of $240,000. You have been paying $1,000 a month off your home loan each month. You now have an extra $1,000 a month available. One option is to start repaying this amount off your investment loan. But a better option is to increase your super contributions.

Let’s say your marginal tax rate is 30%. This means that the $1,000 you have been repaying on your home loan has required you to earn $1,400 or so before tax. This is $16,800 a year. Now that the home loan is repaid, you could consider talking to your boss about sacrificing an extra $16,800 pre-tax into super. This money would only be taxed at 15%, meaning that you would be left with $14,280 in the super fund. Had you instead tried to repay $1,000 of your investment loan, you would only have reduced the debt by $12,000. So, this strategy leaves you with $12,000 more debt than you would have otherwise – but your assets have increased by $14,280. You have actually created an extra $2,280 of wealth.

This strategy will ultimately let you repay the investment loan more easily. Remember, the principal amount of any loan needs to be paid using after-tax dollars. This is the case for both private and investment debt. This means that by running your wages or salary through the lower-taxed super fund, you have more remaining to repay the principal once you reach preservation age. (Preservation age is the age at which you can withdraw money from the super fund and use it to retire debt).

But, even then, you would only withdraw the money and repay the debt if you still had nothing better to do. Read on to the next section where we will explain in greater detail.

3. Buy more investment assets

Instead of repaying deductible debt, you could also use the money to buy more investment assets. This is particularly the case if you are able to buy smaller parcels of asset such as shares or units in a managed fund.

Buying more assets has the same short-term effect on your net asset position as repaying debt would have. Net assets are your total assets minus your total debts, and this is really the best way to calculate your wealth. Consider the following example:

You have an investment debt worth $240,000 and total assets worth $1,000,000. Your net assets are $760,000.

You inherit $40,000. If you use the $40,000 to repay the debt, then the debt drops to $200,000. The assets are still worth $1,000,000, so your net assets are now $800,000.

If you use the $40,000 to buy more investment assets, then your debt stays at $240,000, but your assets increase to $1,040,000. Your net assets are also $800,000.

The two cases seem to be the same, with net assets of $800,000. But it is usually better to own more assets than fewer. Over time, if the assets rise in value, then you will be applying that rise to a larger amount of assets. This is, after all, why you borrow to invest in the first place: because you expect that the increase in the value of your assets will exceed the interest you incur on your debt. So, if asset values rise, then the higher the assets, the more wealth is generated.

Interest only loans

One way to ensure that you only have to meet the interest expense on an investment loan, and you do not have to repay principal, is to use an interest-only loan. As the name suggests, an interest-only loan is one in which borrower only meets the interest requirements of the loan. He or she does not have to repay principal amounts. To give a simple example: if you borrow $100,000 at 6% per year, and you only have to make one repayment a year (this is an illustrative example), then the amount paid to the lender will be $6,000. At the end of the year, you still owe them $100,000.

Interest-only loans can work really well when borrowing to purchase investment assets. By making these ‘investment loans’ interest-only, you avoid having to use cash flow to make loan repayments on debt that is giving rise to tax-deductible interest. Accordingly, ignoring changes in interest rates, the amount of tax-deductible interest does not reduce over time.

By not repaying the principal amount of the investment debt, you ‘free-up’ cash flow to be used for some other purpose. This may include repaying private loans, making super contributions, buying private assets, buying more investment assets, etc.

Interest-only loans are used where you expect the capital value of the purchased asset to increase over time. To give a very simple example: suppose you borrow $100,000 as an interest-only loan and use it to buy units in an index fund. The loan term is five years. After five years, the index fund investment has increased in value to $130,000. You sell $100,000 worth of units in the managed fund, repay the debt and you are left with a debt-free asset worth $30,000.

Of course, there is a danger that the asset will not rise in value – but this is a risk of all investment borrowing and is not specific to interest-only loans. And, where interest-only loans reduce the amount of after-tax interest being paid on all of the borrower’s loans, they can actually serve to reduce the overall risk to the borrower.

ASIC tells us that 2 out of every 3 investment loans is interest-only, while 25% of owner-occupied loans are interest-only. You can read more about interest-only loans on the ASIC website here.

Positive and negative gearing

You have probably heard of the terms positive and negative gearing.

Negative gearing occurs where the income from a geared asset is less than the interest and other holding costs, creating a loss. Investors can usually offset this loss against other income for tax purposes. This creates a tax benefit, in the form of less tax being paid than otherwise, and this tax benefit in a sense adds to the investment return on the asset.

Negative gearing does not make economic sense, however, unless the client expects to earn a capital gain greater than the loss, so that overall the client is better off by making the investment. This capital gain is not taxed unless the asset is sold, and even then usually only half the gain is taxed, provided the asset was owned for more than 12 months.

The most common area in which you see negative gearing is with property investment. The prevailing interest rate for investment property loans is currently around 5 to 5.5%. The prevailing rental yield is around 3 to 3.5%. This means that rent won’t cover interest if the investor borrows all or most of the purchase price of the property.

Have a look at this short video from the team at the Eureka Report. It explains negative gearing quite well:

Positive gearing is where the income from a debt-financed asset exceeds the interest cost. For reasons outlined in the previous paragraph, it is rarely seen in property investment unless the investor has borrowed well below the full purchase price of the investment. Positive gearing can be more common in share investing.

For example, in a December 2012 ASX Investor Update newsletter Paul Zwi from Clime Investment Management observed that National Australia Bank shares offered a high dividend rate of 7.5% or 10.7% grossed up for franking credits. Clients who borrowed to buy NAB shares would have experienced positive gearing: the dividend return was greater than the interest cost.

Positive gearing can work especially well with a debt recycling strategy as outlined above. This is because the income return, such as the dividends, can be used to retire non-deductible debt, while the deductible borrowing is used to pay for anything for which claiming a tax deduction on interest is legitimate.

You will occasionally hear about properties that are marketed as cash flow positive (positive gearing). Be careful. These properties typically either have an artificially-boosted rent (such as guaranteed rent for some limited time) or the purchase price is abnormally low. Both situations should give you cause for concern.

Whether you are positively or negatively geared, your tax liability is worked out the same way. You add the income return (rent or dividends) to your taxable income, and you deduct the interest expense. In negative gearing, you are therefore deducting more than you add, because the interest is more than the rent or dividends. This lowers your taxable income and you have to pay less tax. This reduction in your tax liability can ‘lessen the blow’ of negative gearing. But it only lessens it: you still make a very real loss in the short term and you must compensate for this with a capital gain or you will be worse off. So, the tax benefit of negative gearing is really only the icing on the cake: it is not the whole cake, and you should never make an investment solely or even predominantly because it is negatively geared.

Chapter 5: Special purpose debt: reverse mortgages

Reverse mortgages are loans taken out against property (via a first mortgage), where the amount borrowed is sufficiently small to allow the borrower to capitalize the interest and other charges as part of the loan. Typically, the loan remains unpaid until the asset is disposed.

Who Does A Reverse Mortgage Suit?

Reverse mortgages are typically undertaken by older people, who are ‘asset-rich but cash poor.’ They own their home, with no debt on it, but find that their income is less than they need/would like to live

What are the Benefits of Reverse Mortgages?

The most obvious benefit is that the older home owner is able to finance a better quality of life, without selling their home. Aged pensions are not generous. For a single person, the maximum aged pension in Australia is $877 per fortnight. For a member of a couple, the maximum aged pension in Australia is $661 (each) per fortnight. These are not large amounts. The average annual wage for working Australians is around $1,400 per fortnight.

The reverse mortgage allows a borrower to ‘free up’ some of their capital, allowing them to enjoy the benefits of the wealth they have accumulated while still living in their own home, and continuing to benefit from any appreciation in the value of that home.

Another major benefit of a reverse mortgage is that it reduces the need for older people to sell their homes and move to something cheaper. Such sales can be disadvantageous for at least two reasons.

The first of these reasons is lifestyle. Urban lore is full of stories of older people whose health has started to deteriorate when they have moved out of a home they have lived in for many years. The move can be disorienting, both intellectually and emotionally, and moves into ‘facilities’ such as aged care homes or retirement villages can mean different things to different people. Some older people embrace such moves. But for others, the move can be a very real demonstration that they are approaching the end of their life. It is quite dispiriting and anecdotal evidence suggests it can even hasten the end of a person’s life.

The second of these reasons is financial. Older people who have owned their own home for a number of years possess an asset which is worth more than they paid, even when the purchase price is adjusted for inflation. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, residential property prices rose 23.7% through the year to December quarter 2021. This was the strongest annual growth since the Residential Property Price Index series began in the September quarter 2003. This was well in advance of the inflation rate, meaning that the real value of property rose substantially across the period.

Hopefully you are familiar with the concept of compound returns, whereby the rate at which a growth asset appreciates, as a percentage of the purchase price, is greater the longer the asset is held. This is because the later growth includes ‘growth on growth.’ Selling the family home ends this compounding. This slows – in fact in many cases ends – the rate at which the individuals’ wealth increases. In addition, it entails selling costs, and if another property is purchased, purchase costs such as stamp duties as well. These costs permanently diminish the wealth of the older person.

By taking a reverse mortgage, the older person can continue to receive the wealth enhancing benefits of home ownership.

What Are the Potential Disadvantages of a Reverse Mortgage?

Reverse mortgages are a debt product. As such, the success or otherwise of a reverse mortgage will depend on the behaviour of the borrower. It will also depend on the conduct of the lender.

The most obvious potential disadvantage of a reverse mortgage is that the debt grows. This is because the borrower typically does not even pay off the interest. Thus, the debt might grow to the point where it exceeds the maximum amount the lender is prepared to lend. Such a situation might see the lender foreclose on the loan, forcing a sale upon the borrower. This situation is obviously more likely in the event of higher interest rates, which may also coincide with a fall in property values, meaning the sale occurs at exactly the wrong time.

The prospect of the debt getting out of control is largely derived from the amount borrowed. For this reason, people undertaking a reverse mortgage need to understand that the mortgage is not a bottomless pit. The borrower must ensure that they borrow a small amount relative to the value of the house. Of course, the need for discipline is the same with all types of debt. But it is especially the case for reverse mortgages, where interest is capitalized.

That said, the obvious risk of reverse mortgages is such that there are substantial rules governing the behaviour of lenders in this segment of the market. These rules were released in 2012. You can read about these rules, and also read further about reverse mortgages, on the ASIC website here.

A commonly cited disadvantage – albeit one that does not really stand up under close scrutiny – is the idea that the debt reduces the wealth of the individual. In the first case, even if the strategy did reduce their wealth, given that the borrower is typically near the end of their life, this situation is not such a problem. Why shouldn’t an older person enjoy some of the benefits of the wealth they have created over the years? You can’t take it with you, as they say.

Notwithstanding this, when done properly the reverse mortgage will often actually increase the wealth of the individual, in the same way that leveraged investments generally increase wealth. Because the borrower retains ownership of what is typically a growth asset, they retain access to the long term capital growth of that asset. This long term capital growth typically exceeds the interest expense each year, especially considering that the debt is substantially lower than the value of the house.

Accessing a Reverse Mortgage

Not all lenders offer a reverse mortgage. Because the interest and other fees are capitalized, the lender has to wait to get its money. This extends the period of the loan, which may introduce a risk premium from the lender’s point of view. In addition, some lenders prefer not to lend to borrowers with low incomes, regardless of the circumstances.

Therefore, you may need to shop around for a lender who is prepared to offer a reverse mortgage. In some cases, lenders might only be prepared to get involved if offered further security, such as a guarantee from some third party. The obvious candidate is the borrower’s children, who stand to inherit the house when their parents die. This would be an example of children taking an involvement in their parent’s affairs while their parents are still living. If prudent and possible, this involvement can be a good thing for all concerned.

Of course, in situations where the children have sufficient resources, a formal lender may be unnecessary. The children, either in their own right or via a family trust or similar vehicle, could make the loan to the parents. This strategy would usually need to be formalized, to ensure that the parents retain their rights to the full aged pension, etc. The use of an adviser is encouraged in such cases. Liaison with Centrelink would also be prudent, to ensure their rules are not breached.

Potential Problems with Reverse Mortgages

One of the most common problems for reverse mortgages can be unwillingness on the part of elderly borrowers. Older people often belong to a cohort that was conditioned to believe that any debt is bad debt. They will often fail (or refuse) to grasp the mathematics presented by the models above.

But then, they are not the only ones. About twenty years ago, Adrian, one of the key staff at our AFSL, was working for the Victorian Department of Human Services. His responsibility was to manage the funding for various aged care facilities in the northern region of Melbourne. Another part of the service provided case management services to frail and disabled people in the same region. One day a case manager approached Adrian to describe a situation with an elderly client of theirs. This man, in his eighties, needed a $3,000 refurbishment of his bathroom to allow him to stay in his own home, in a recently gentrified inner suburb. They wanted to know if Adrian knew of any funding that he may be able to access.

There was no funding available, but at the time vacant blocks of land in that area were selling for $400,000. When Adrian established that this man owned his home with no debt, he suggested a reverse mortgage. The social worker to whom Adrian was talking was aghast at the idea of asking this man to take on debt to finance the works, and did not make the suggestion. Thus, for the want of a loan of $3,000 secured against a $400,000 property, an old man was forced to leave his home of forty years and enter aged care.

From a personal point of view, this was a tragedy – the man left a much loved home unnecessarily and moved into care. From a financial point of view, it was a disaster. Over the next five years, properties in that part of the world doubled in value. Had the man borrowed $3,000 to finance the works, he would have retained an asset that increased by $400,000 over the next five years.

Chapter 6: Some general thoughts on borrowing

Finally, we thought we should let you know some other general thoughts about borrowing. These thoughts come from our specialist training and experience in financial planning and we hope that they will be of use to you as well.

Your bank manager is not your friend

Your bank manager is your opponent. The game of getting a loan might be played in a good spirit – but he or she is on the other team. The bank’s – and therefore the bank manager’s – income is your cost. He or she sits on the other side of the table and wants you to pay as much as possible for the money you borrow. You can be friendly but do not be friends.

Look for the cheapest loan possible

The interest reduces the net return on the investment (by which we also mean your investment in your family home). The higher the interest rate, the lower the net return. So it makes sense to minimise the interest paid on a loan. Our observation is that clients are usually far too polite about accepting interest rates that are higher than they need to. Remember, the Bank Manager is not your friend.

Ensure interest is tax deductible

Try always to ensure that the interest is tax deductible. For this to be the case, the borrowing must be connected to assessable income.

When debt is used to buy or hold an investment the interest is deductible.

If you have private, non-deductible debt as well as investment debt you should separate your loans so they are not used for a mix of private and investment purposes. Quarantine your investment loans. Don’t mix them up. This makes it clear which loan was used for investment purposes, and helps ensure the interest is tax deductible.

Get an appropriate interest rate

Make sure that your interest rate is not too high. Some banks try to charge higher rates than necessary. The person at the bank is usually on commission (often that includes the bank manager), so the incentive to help the borrower (ie you) get the lowest rate possible may not always be high.

Sometimes a client will take a loan in the name of the trustee of his or her family trust, or some other trust. This trustee is usually a company, with the letters ‘Pty Ltd’ after the name. Some lenders will assume that the loan is a business loan and try to apply a higher interest rate. Don’t agree to this. Banks will lend at home loan rates to a company or trust if the underlying security is a residential property.

In summary, if the security is residential property the home loan interest rate should apply. This can require the adviser to advocate for the client.

The home as security for a loan

Any asset can be used to secure a loan. It does not have to be the asset bought with the loan. For example, an investor may mortgage their home to buy shares. The interest will be deductible because the purpose of the loan is to earn assessable income, in the form of dividends.

The interest rate will be lower because the home is the best security for a loan.

This is the cheapest way to finance an investment. Sometimes clients worry about using the home as security for a loan. They are concerned the home may be lost if the investment goes bad. This should not really be an issue. The issue is the net wealth of the borrower. Net wealth is the difference between what the borrower owns and what the borrower owes. If a borrower owes $100,000 on a $500,000 property, for example, and there are no other assets, then the net wealth is $400,000.

Provided the overall net wealth exceeds the value of the home, the home will not need to be sold. The other assets can be sold to pay off the liabilities. Consider an example:

Susan owns a home worth $500,000 and has $100,000 cash saved. This means that she has $600,000 in net wealth. She borrows $240,000 against her home and uses it to buy index-based managed funds (using dollar cost averaging, of course). Susan now has $840,000 in assets and $240,000 in debt – her net wealth is still $600,000. If something happens and she needs to repay the loan she can sell the index funds. She will not have to sell the home. If the value of the index funds falls by a large amount – even 50% – then her net assets will fall to $480,000.

The key, then, is to always allow a buffer or margin of safety when borrowing to buy assets.

Consider also the case where an investor borrows against the value of an investment asset that falls in value. The lender forces the asset to be sold – and then takes further action against the investor if selling the asset does not repay the entire loan. If that means that the investor ends up having to sell or mortgage their home to repay the debt, then that is what the lender will pursue. The fact that the home was not used as security for the loan will not prevent the lender from taking action against the borrower, who may end up having to use their home to repay the debt anyway.

There are some structures that can be used to ‘protect’ assets such as the home. If you think you need something like this, then let us know and we can provide specific advice. But be aware that lenders also know how these structures work and will simply not make a loan if they think there is a chance that the loan will not be repaid.

In summary, the advantage of lower interest rates, which means higher net returns and less risk, often justifies using the home as security for a loan. Just keep the debt to prudent levels and use it to buy well-regarded assets.

Pay the interest

The ATO does not like allowing deductions for un-paid interest. There is some doubt as to whether this is correct at law, but one thing is certain: it’s simply easier to pay the interest on time than it is to argue with the ATO. So, make sure all interest is paid, and not capitalised, if you are claiming a deduction.

Study the contract

Get advice. Research the costs before you sign the contract. Make sure you know the interest rate, the principal repayment rate, the administration costs and the penalties for early repayment. Shop around. The first offer is unlikely to be the best offer.

Make sure your application is clear and to the point

Support it with accounts, company searches, business plans and similar documents where necessary. These materials are best included as appendices to the main application as they may cloud the message you are trying to deliver. If the loan is for business or investment purposes, stress this, as it may be relevant if the ATO questions the deductibility of any interest claimed on the loans down the track.

Ensure you have the cash flow for repayments

Ensure your finance application shows that all repayments can be met out of your existing and expected cash flows. If asset sales are contemplated in the short or medium term say so, as this is relevant to your capacity to service the debt. Financiers may not be impressed if the repayment of principal depends solely on the sale of the object investment.

Do not borrow too much

Most banks work on a debt-to-equity ratio of about 70:30. In working out the value of your equity they discount historical cost by factors representing their expected resale experiences. Take account of these discount factors before you commit yourself to a transaction. Ensure your finance application includes all relevant materials, including financial information that does not necessarily favour your application. If something goes wrong later and the lender finds out that information was withheld, problems will arise.

And if you have to fib to get a loan, you should not be getting the loan.

Keep the communication channels open

If something does go wrong, tell the lender immediately. This is important because lenders often base their recovery actions on their perceptions of how the borrower behaved. If your word is your bond, then you will get much better treatment if an unexpected situation arises. Because trust has been established, the lenders are more likely to help out if needed. Open and honest communication is the key to building this sort of a relationship, and once it is created, you shouldn’t waste it.

Lenders will be reasonable if you are reasonable, so play with a straight bat at all times.

Offer subject to finance

If you are borrowing to buy property, consider making your offer subject to finance from a specified branch of a specified bank at a specified time, say a month. If something goes wrong you will probably not lose your deposit. If you change your mind within the specified timeframe you may be able to “arrange” for your finance application to be refused so you can get your deposit back.

But make sure that the finance condition specifies which bank and even which branch of that bank. If you do not do this the vendor may arrange finance for you through a lender you would not have chosen to use.

Hints for income tax time

Consider a facility such as a fully drawn advance, or an overdraft, that allows you to pre-pay interest. Pre-paid interest is generally tax-deductible in the year it is pre-paid, provided the pre- payment period does not extend for more than 13 months.

Non-deductible debt, which is not connected to a business or investment activity, is the most expensive debt. Every $1 of interest accounts for up to $2 of pre-tax income. A basic tax planning strategy is to pay off expensive non-deductible debt as soon as possible and defer paying off cheap deductible debt for as long as possible. If you have a 15 year home loan of $200,000 and a 15 year investment loan of $200,000 it makes sense to pay off the home loan at twice the usual rate and pay nothing on the investment loan.

Keep your banks separate

Separate your financiers. For example, consider having your home loan with the ANZ, your business loan with the National Australia Bank and your credit card with Westpac, and do not let them have cross-securities. Each bank should have security over just one asset.

This may sound messy, but if something goes wrong it will be a lot harder, if not impossible, for each bank to tie up the various securities provided to them.

Let someone do the work for you

Use a consultant who is experienced in dealing with banks and who can represent your interests competently. The consultant should have a good handle on both the accounting and legal aspects.

Consider using a finance broker. They are constantly in touch with the market. This saves you time dealing with lenders and saves you money because in most cases the broker can get you a better interest rate. Normally using a broker does not cost you anything because the lender pays the broker, not you. Because dealing with a broker is typically easier for the lender than dealing with you directly, the lender saves money and this is the money used to pay the broker; you do not pay higher costs because a broker is involved.

We can assist you here, and we guarantee that you will not pay more for your loan if you obtain finance help through us.